Why we're racing robots

And it's not why you think - inside A2RL Season 2

Thank you for being here. You are receiving this email because you subscribed to Idée Fixe, the newsletter for curious minds. I’m Toni Cowan-Brown, a tech and F1 commentator. I’m a former tech executive who has spent the past five years on the floor of way too many F1, FE, and WEC team garages, learning about the business, politics, and technology of motorsports.

⏳ Reading time: 9 minutes

18 months ago, I discovered A2RL - the Autonomous Racing League - and since then, I’ve wanted to work with them to better understand their mission, what they are building, the actual technology and why they are working on this. Last weekend, this was all made possible as I joined the A2RL press trip for their second-ever race.

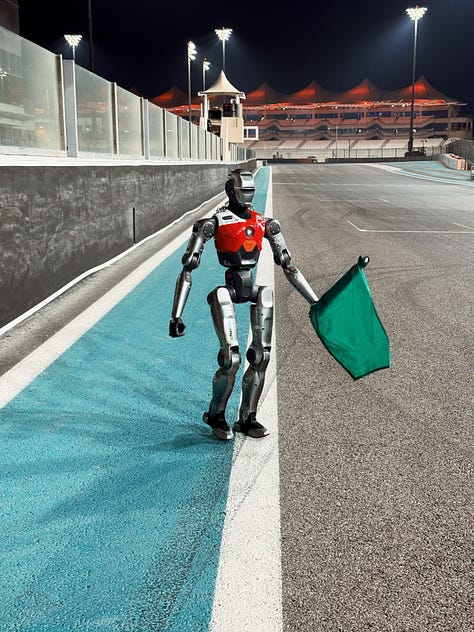

Under the lights at Yas Marina Circuit, I watched six fully autonomous (not remotely controlled as I initially thought) race cars battle wheel-to-wheel at speeds exceeding 250 km/h. No drivers. No remote controls. Just pure AI making split-second decisions at the absolute limits of physics. When Germany’s TUM and Italy’s Unimore traded the lead through sweeping corners with less than a second between them, it was easy to forget these were algorithms, not athletes. And then you caught a glimpse of humans looking out onto the track, just waiting for the cars to make their next move, and you were swiftly reminded that the humans weren’t in control here.

The Autonomous Racing League’s second season grand final wasn’t just spectacular - it was necessary. And understanding why requires rethinking what we mean by “testing” in the age of autonomous vehicles.

The laboratory that moves at 250KPH

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about autonomous vehicle development: most edge cases - those unexpected, rare scenarios that systems aren’t designed to handle - will never appear in conventional testing. You can simulate millions of scenarios, log billions of road miles, but you’ll still miss the critical moments where perception systems fail, where decision-making algorithms freeze, where the real world refuses to fit the training data. Racing changes this equation entirely, as Stephane Timpano, CEO at Aspire, reminded me.

A2RL creates an extreme testing ground to stress test and optimise autonomous vehicle software, enhancing safety and reliability. On a racetrack, the edge cases arrive constantly. Cars must make dozens of high-stakes decisions per lap: when to brake, how to plan overtaking manoeuvres three corners ahead, how to react when another vehicle makes an unpredictable move. Each race places AI systems under stress that future autonomous vehicles will face on public roads, from GPS dropouts and sensor faults to unpredictable inputs and split-second decisions at 250 km/h.

Mastering these challenges on the track, where speeds are higher and reaction times shorter, leads to safer autonomous vehicles on the road. The data generated alone is staggering. During this weekend’s race, TUM’s car “HAILEY” and Unimore’s challenger processed terabytes of information while executing complex overtaking manoeuvres that would have seemed impossible eighteen months ago. When Unimore collided with another car while attempting an aggressive pass, it wasn’t a failure - it was valuable data about the precise boundaries where autonomous decision-making breaks down under pressure.

Why competition accelerates everything

Which leads us to the first big question I have gotten repeatedly since last weekend: Why make it a race? Why not just test on empty tracks? Because competition does something that no amount of isolated testing can replicate: it creates pressure. And pressure reveals truth.

Consider the trajectory: In just 18 months, teams have gone from standing still to delivering lap times that were faster than what humans have set with precise consistency, and mastering complex overtakes - progress that can take years. During sessions out on track, the autonomous cars not only closed the gap with human benchmark lap times but surpassed them, moving from minutes behind to mere fractions of a second ahead.

This acceleration isn’t accidental. Competition is more than a spectacle; it’s a strategic tool to accelerate trust, innovation, and leadership. When eleven international teams are competing for $2.25 million with global attention watching, the engineering intensity reaches levels impossible to sustain in pure research environments.

The competitive format creates several unique advantages. First, it establishes clear, objective benchmarks. There’s no arguing about whose system is “better” when lap times and race positions are measured to the millisecond. Second, it forces rapid iteration. Teams had intensive qualifying sessions and virtual SIM Sprints that enabled them to explore challenging scenarios before the real-world event, compressing development cycles that might otherwise take years. Third - and perhaps most importantly - it creates a community of shared learning. The teams aren’t just competitors; they’re collaborators advancing a common goal. Teams are connected with top industry suppliers in the automotive sector, creating knowledge transfer pathways that accelerate adoption across the industry. And we, the audience, get a glimpse into this immense science project.

The testbed, not the threat

Let me be clear: nobody (and I say this as someone who very rarely uses absolute statements) thinks autonomous race cars will replace Lewis Hamilton or Max Verstappen. This isn’t about eliminating human motorsport any more than calculator development was about eliminating mathematicians.

A2RL exists at a different level entirely. As H.E. Faisal Al Bannai, who envisioned the league, explained: “A2RL shows what happens when bold ambition meets scientific discipline. It is more than a race—it is a testbed accelerating the future of autonomous systems while building public trust in the technologies that will soon move through our cities, skies and industries”.

The parallel to early automotive history is instructive. Over a century ago, as society shifted from horse-drawn to motor-powered vehicles, there was public doubt about the safety and reliability of the new technology. Motorsport racing was organised to showcase the technological performance and safety of these horseless carriages. Similarly, autonomous racing serves as the modern arena to prove reliability as driverless cars begin to hit the streets.

This weekend’s “Human vs. AI” exhibition perfectly illustrated this philosophy. Former Formula 1 driver Daniil Kvyat lapped Yas Marina in 57.57 seconds while TUM’s HAILEY managed 59.15 seconds. Just 1.58 seconds separated human and machine. Eighteen months earlier, that gap was ten seconds. The trend line is unmistakable, but more importantly, the exercise demonstrated that autonomous systems are rapidly approaching - not replacing - human capabilities in controlled environments.

As Daniil Kvyat told me, “This project really stood out to me. It’s been great to see the technology evolve over the past year and get closer to the human limit. Hopefully, someday this tech can bring its potential into other aspects of society.”

From track to street: the transfer that matters

The real question isn’t whether autonomous race cars are impressive (they are), but whether the technology translates to safer roads. And here, the evidence is compelling.

Every technological leap in motorsport history - from disc brakes to hybrid powertrains - eventually filtered down to consumer vehicles. The focus is on how to get to a world where we have high-speed autonomy, cars and trucks that can move on highways at speeds greater than 160 kph.

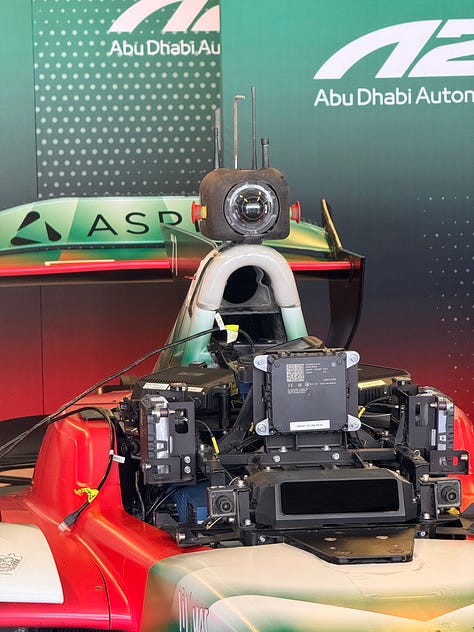

The technologies being refined at A2RL address fundamental challenges in autonomous systems. Perception systems must classify objects at extreme speeds. Planning algorithms must predict the behaviour of multiple agents simultaneously. Control systems must execute manoeuvres at the edge of physical limits while maintaining safety margins. These aren’t race-specific problems - they’re precisely the challenges autonomous vehicles will face in real-world traffic, just compressed in time and intensity. Consider the typical autonomous vehicle edge cases that researchers struggle with: sudden changes in road conditions, unpredictable movements of other road users, GPS signal loss, sensor failures, and split-second decision-making under uncertainty. Racing creates environments where these scenarios appear constantly and must be handled correctly. The competitive pressure ensures that solutions are robust, not just adequate.

The EAV-25 race cars that teams compete with represent this transfer potential. Built on modified Dallara Super Formula chassis with 450-horsepower Honda engines, they feature comprehensive upgrades: advanced steering systems, improved Global Navigation Satellite Systems, 5G antennas, motorsports-specification wiring, secondary safety systems, and sophisticated sensor arrays. While autonomous vehicles on public roads will use electric powertrains, the software and decision-making architecture being developed translates directly.

As autonomous vehicles continue their slow, careful deployment in controlled urban environments - think Waymo in San Francisco, Zoox robotaxis in Las Vegas or Cruise’s supervised testing in Phoenix (which has now ended) - the gap between what’s possible in theory and what’s acceptable in practice remains wide.

Racing compresses that gap. It forces systems to handle uncertainty at speeds where mistakes have immediate, visible consequences. It generates datasets that capture scenarios too rare or dangerous to test on public roads. It creates competitive pressure that drives innovation faster than pure research could achieve.

The infrastructure of innovation

What struck me most about the whole event wasn’t just the technology on track - it was the ecosystem around it. The event happened during the Abu Dhabi Autonomous Week, a six-day convergence of researchers and industry experts. Over 8,000-10,000 spectators filled the grandstands, while a parallel STEM competition engaged 140 students across the UAE racing 1/18th-scale autonomous cars. This structure reveals the broader strategy. For Abu Dhabi, A2RL serves as both an R&D accelerator and a strategic signal of intent, aligning with the country’s ambition to diversify its economy, attract global talent, and establish itself as a trusted testbed for emerging technologies.

The progress is measurable. Before A2RL’s debut in 2024, no more than one car had driven autonomously on a racetrack simultaneously. The inaugural event managed four cars. Season 2 achieved six cars racing wheel-to-wheel, executing complex overtakes and maintaining a competitive pace for 20 laps.

Daniil Kvyat, reflecting on the pace of advancement, captured it perfectly: “Looking back to when A2RL development first began a couple of years ago, with perhaps minutes between a human driver and the AI car, down to 10 seconds in our first showcase last year, and now we are seeing performance within fractions of a second—the technology progress is staggering”.

The deeper value beyond the spectacle

But perhaps the most important contribution of A2RL isn’t technical at all - it’s psychological. It certainly was for me.

Public acceptance of autonomous vehicles remains a significant barrier to deployment. Surveys consistently show people remain sceptical about ceding control to algorithms, even when presented with safety statistics. Racing addresses this by making autonomous systems visible, understandable, and - crucially - fallible in controlled environments.

When an autonomous race car executes a perfect overtaking manoeuvre, spectators witness capability. When one makes a mistake and crashes, they witness honest limitations being identified and addressed. This transparency builds trust more effectively than any marketing campaign or safety report.

The format also creates heroes, just not human ones. Teams develop followings. Algorithms earn reputations. The narrative structures of competition - underdogs, dominance, surprise upsets - make the technology relatable and engaging. TUM’s back-to-back championships establish them as the team to beat. Unimore’s aggressive but ultimately unsuccessful challenge creates anticipation for their next attempt.

As I left the Yas Marina Circuit after the race, watching teams pack up their equipment and download final data logs, I kept thinking about what happens next. Now what?

The autonomous vehicles being tested on public roads face different challenges than race cars: pedestrians, cyclists, construction zones, unclear signage, weather conditions, and human drivers behaving unpredictably. But the fundamental problem remains identical: how do we build systems that handle the unexpected safely and confidently?

A2RL’s answer is elegant: create environments where the unexpected happens constantly, measure everything, iterate rapidly, and make the whole process public. It’s not the complete solution to autonomous vehicle deployment - nothing could be -but it’s an essential component. The real achievement of A2RL Season 2 wasn’t TUM’s victory or the impressive lap times. It was demonstrating that competitive pressure, transparent development, and extreme testing environments can accelerate technology in ways that traditional research cannot match. And this is something that Stephane Timpano has been unapologetic about with this project.

And critically, it proved that we can develop autonomous systems without diminishing human achievement. The goal isn’t to replace drivers but to create tools that make transportation safer, more efficient, and more accessible. As autonomous vehicles slowly and carefully make their way from test tracks to city streets, initiatives like A2RL provide the platform where algorithms are forged under pressure. The technology emerging from these competitions won’t just make faster race cars - it will make the autonomous vehicles sharing our roads more reliable when they encounter their own edge cases at 50 kph on a rainy Tuesday morning.

That’s why we’re racing robots. Not because it’s spectacular (though it is), but because competition accelerates innovation in ways nothing else can match. The spectacle is just a bonus. Although one final question I did have was whether this would be an interetsing spectacle to watch, and it was.