Idée fixe 4.3: Formula One

Part Three: The bizarre world of F1 sponsorships and big tobacco (bonus piece)

You are receiving this email because you subscribed to Idée Fixe - the weekly newsletter for curious minds. Thank you for being here. If you are new to Idée Fixe, welcome. I’m Toni Cowan-Brown and each week I’ll share with you some insights on the ideas that matter and dominate our minds.

Idée Fixe #4: Formula One 🏎 🏁

This is a little extra to my two-part guide into the exciting world of Formula One. Mostly because I went down a rabbit hole when researching Formula One sponsors and started looking at the history between F1 and big tobacco, as well a the current landscape with alcohol and energy drinks. And let me tell you, it’s absolutely fascinating.

👉 Part one: The Basics and The History of Formula One

👉 Part two: Technology, Strategies and Fearless Drivers.

🖐 Heads up part one is roughly 2,900 words and will take you approximately 9 minutes to read.

First things first, last Sunday we finally kicked off the F1 2020 season. And what a race with only 11 drivers actually making it to the checkered flag. 🏁 For people watching their first-ever F1 race, I can confirm that this race was a real treat.

This was amplified by the fact that it had been 217 days since the last race in Abu Dhabi, which apparently is the longest time between races in Formula One history.

The Sponsorships and The Money

Formula One teams currently get their budgets from three main sources:

Team owners. This is true in most cases but not all. Take Renault, for example, which is partly owned by the French state (15.01% to be exact).

Prize money. Formula One’s annual prize money payout (which is public knowledge) came to $913 million in 2019.

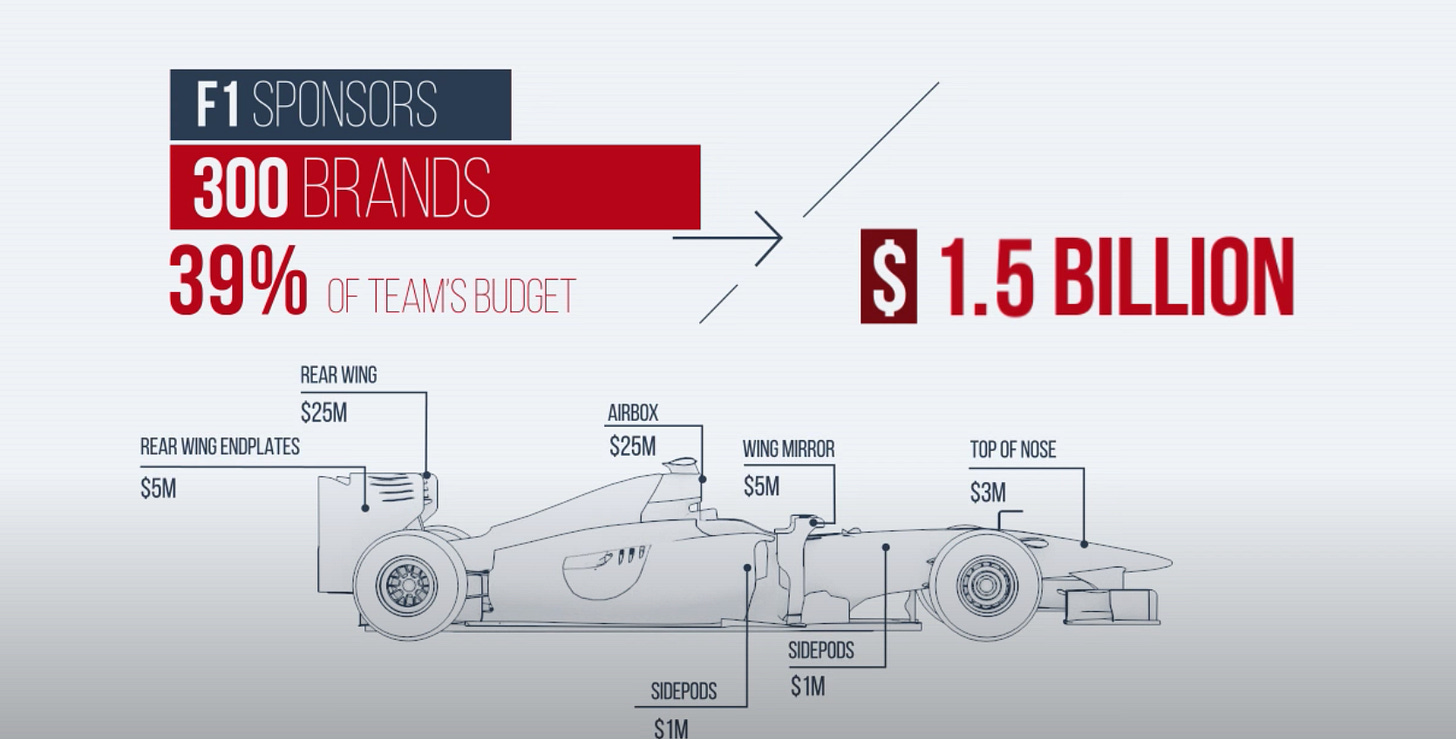

Sponsorships and advertising. This is where the bulk of the money comes from, covering almost 40% of a team’s budget and this is the source of income we will be looking into today.

Supplying technology and services inside and outside of F1. I know I mentioned there were three main sources but actually there is a fourth source, depending on how you look at things. Although still fairly small in comparison, it’s one worth looking into further.

There are different types of sponsors in Formula One. You have the title sponsors of F1 itself (those brand names that you see everywhere around the track and paddock (can be different sponsors in different countries), you have the team sponsors (often visible on the outside of the cars, on the drivers’ helmets and outfits) and many drivers also have sponsorship deals themselves.

It’s definitely a sport with (sometimes) excessive amounts of sponsorships and paid-for branding. But Formula One’s business model is essentially built on and around sponsorships, or rather it was until recently. We will get to that shortly.

In F1 there is a direct correlation between how much a team wins (i.e. how many podiums they are on) and how much funding and sponsorship they can attract. For advertisers, visibility and prestige are more or less the only reasons to sponsor F1. There really isn’t any other reason to do so and the ROI is quite hard to calculate. But there is no doubt that sponsors really do fuel F1 with some $30 billion in funding.

The cycle goes a little like this; the more money you have, the more you can spend on your car (although the new 2021 rules ensure there is now a budget cap on this spending) and spend on your drivers (currently exempted from the spending limit). Although there have been recent talks about capping the drivers’ salaries too. It’s also about who you are able to attract - the more money you have, the more you can attract the best talent - both in terms of drivers but also engineering - which obviously has a direct impact on the sponsors you attract in return. And the circle starts all over again.

Up until recently, there has been a significant gulf between the team that spends the most and the team that spends the least (+/- $300million). Although this funding gap forces F1 teams like Haas to get creative, I don’t think any team would disagree with the premise that those with bigger budgets are at an advantage. And just in case you were wondering, it roughly costs $11 million to build an F1 ‘racing machine’- with approximately half of that going to the engine alone.

And like with everything, when big money is involved you generally find a fascinating cast of characters and some wild stories fit for the Hollywood screens.

The tobacco industry’s desire to stay in F1 and the diversification of revenue streams.

Back in the ‘good old days’ Formula One was very much sponsored to a large extent by the tobacco industry. However, gone are the days of such large sums of money being poured in these types of sponsorships. Actually, this is mostly true across all industries - the landscape and business models have evolved and the sponsorship model seems to be in a transition phase.

Or as Mark Gallagher puts it, today there is a new business model in F1 which is the technology transfer model. “We’ve had to move to a world where Formula One teams can sell technology, goods and services into industry or into the public, as a way of generating revenue.” As mentioned in part two, some works teams will sell their engines (and other parts and technology solutions) to other F1 teams to create a new revenue stream.

However, as Gallagher also points out, “at the moment, the diversified engineering and technology businesses in F1 are not even close to replacing the tobacco revenue from the old days”. This is the fourth revenue stream I mentioned right at the start of this piece - and it’s yet to be considered a main source of revenue but the teams would do well to amplify this source of revenue.

Note: This is probably worthy of another post but it’s actually quite fascinating to think about how the F1 industry as a whole has reinvented itself over the past couple of decades and still is, mostly out of necessity. This technology transfer model spills over far beyond the race tracks and race weekends as F1 is at the cutting edge of a plethora of technology spaces such as data analytics & analysis, aerodynamics, fuel and battery efficiency...

Just like in any industry, the key is going to be the diversification of your revenue stream. I for one would take a crash course from any F1 team on team efficiency - don’t forget they have mastered how to change four tires in under 2 seconds. What can you do in under 2 seconds?

I am still young enough (or old enough depending on how you look at things) to remember that when I attended my first F1 Grand Prix (at Spa Francorchamps, in Belgium), Marlboro was still one of the biggest sponsors and their logo was slapped everywhere - around the track, on cars, on the apparel, on pillows… You name it, it probably had the Marlboro logo on it. The Marlboro logo was so present that when my dad showed me, age 5 or 6, a plastic bag with a red chevron on it (no words or logo) and asked what it was about. I replied almost immediately, ‘cigarettes’. 🚬

And then in 2006, the FIA banned tobacco advertising and sponsorship in F1, although it was initially confirmed in November 2001. This was a direct result of the European Union introducing a ban on tobacco advertising initially passed by the European Parliament and Council in 2003 and taking effect in 2005.

The Tobacco Advertising Directive (2003/33/EC) introduces an EU wide ban on cross-border tobacco advertising and sponsorship in the media other than television (which was prohibited in 1989). The ban covers print media, radio, internet and sponsorship of events involving several EU countries, such as the Olympic Games and Formula One races.

Free distribution of tobacco is banned in such events. The ban covers advertising and sponsorship with the aim of direct or indirect effect of promoting a tobacco product.

Because F1 is one of the most-watched events in the world (after the Olympics and the World Cup), it provided the tobacco industry (one of its main sponsors) unparalleled marketing and exposure. The ban had a massive financial impact on five major F1 teams for which tobacco was a big source of revenue - namely McLaren (West), Benetton (Mild Seven), Ferrari (Marlboro), Jordan (Benson and Hedges), and BAR (British American Tobacco).

It’s interesting to look back at comments made in 2003 such as this one from FIA president Max Mosley who had this to say - a ban could result in there being only a handful of F1 Grand Prix in Europe in future. Today, a big number of Grand Prix still take place in Europe and the 2020 calendar is actually happening, so far, solely in Europe. I would also argue that the expansion of F1 outside of Europe has been good for the business overall - diversifying the markets in which you have an audience is part of the diversification of the revenue stream.

As a result of the EU’s Tobacco Advertising Directive, tobacco advertising in F1 was nearly totally eradicated. That being said, big tobacco got very creative and clever over the years.👇As pointed out in the video below (by Donut media).

In 2007, the Marlboro logo on Ferrari cars was replaced by the ‘barcode’ design (without the word Marlboro) which Ferrari claimed was part of the livery and not a Marlboro advertisement. What initially looked like an innocent barcode, very quickly turned out to be a clever way to evoke the well-known Marlboro chevron to millions of people’s subconscious as the cars drove past them at 300kph. It was later concluded that the controversial ‘barcode’ is actually “alibi Marlboro logos and hence constitute advertising prohibited by the 2005 EU Tobacco Advertising Directive” and was later removed from the cars.

In 2019 we saw tobacco brands returning to F1 in a variety of stealth ways. This same year, and as a result of the two new branding campaigns discussed below, the WHO argued that more can and should be done.

There are two case studies worth looking at in further detail: The Mission Winnow campaign with Scuderia Ferrari (1) and the A Better Tomorrow campaign with McLaren (2).

🧐The Mission Winnow story

Philipp Morris International (owner of Marlboro) has been a long-term partner of Ferrari and returned as such during the 2018 season. Thus PMI (Philipp Morris International) is still sponsoring F1 to this day but simply doing so under a different name - enters Mission Winnow.

The Mission Winnow (get it - Win Now 💡) campaign is focused on promoting its research on “less harmful alternatives to cigarettes”. Most Will argue that this PMI initiative is simply an attempt to circumvent laws that prevented big tobacco from advertising in Europe. They will argue that this is merely an awareness campaign.

From what I could gather, PMI remains Ferrari’s title sponsor since Mission Winnow and Ferrari announced a multi-year partnership that will last until the end of the 2021 season (extended in 2018).

That being said, Mission Winnow feels absent from the Scuderia Ferrari website today - it’s not listed with the other partners and where there clearly was once a partner page dedicated to the Mission Winnow partnerships, it’s now a 404 Error Page. There is a page dedicated to laying out the tech specs for the 2020 SF1000 and there you can clearly see the Mission Winnow emblems on the rear wing, engine cover and nose of the car (see below).

Apparently, as Ferrari unveiled its 2020 SF1000 car with the Mission Winnow advertising on it, things didn’t go down too well with Italy’s best-known consumer rights group.

However, none of these Mission Winnow emblems were present during the kick-off race of the 2020 season in Austria last weekend (3-5 July), as you can see below from a screenshot taken during the race.

All of the above is in stark contrast to the Mission Winnow website which has a dedicated Scuderia Ferrari page that you can easily find on the top right-hand corner of their homepage.

“A story of continual reinvention: The most successful team in Formula 1 History, constantly winnowing and innovating.” 🤷♀️

👉 Read more about how Mission Winnow undermines sports sponsorship bans (a very long but very detailed piece).

🧐A Better Tomorrow’s story

PMI isn’t the only tobacco organization still present in Formula One today. In 2019, A Better Tomorrow campaign was introduced as a title sponsor for McLaren. You may not be surprised to hear that A Better Tomorrow is actually owned by British American Tobacco (BAT) which is a multinational cigarette and tobacco manufacturing company. This is actually their first involvement in F1 since 2006 when they withdrew following the EU ban on tobacco advertising.

A Better Tomorrow campaign is focused on promoting electronic smoking alternatives (aka. vaping). Their partnership is apparently grounded on tech and sharing of technical expertise and best practices.

Although BAT secured a livery deal with McLaren with the Better Tomorrow slogan on the sidepod (the new design was unveiled in March 2020), it isn’t the main sponsor, only a key sponsor. Similarly to PMI and Ferrari, BAT signed a multi-year global sponsorship with McLaren in 2019.

BAT’s involvement in F1 actually goes back a long way and is probably involved in one of the ultimate expressions of F1 as a ‘tobacco marketing platform’. In 1998, BAT announced that it would fund the British American Racing (BAR) team with two cars - one in the 555 colours and the other in a Lucky Strike Livery (two cigarette brands owned by BAT). BAR competed as a constructor team between 1999 and 2005 but never won any races. In November 2004, Honda (the Japanese automobile manufacturer) purchased 45% of the team, and then in 2005, they purchased the remaining 55% becoming the sole owner.

Although, both PMI and BAT aren’t pushing tobacco products per se, many have argued that what they are doing contradicts F1’s rules prohibiting the promotion of tobacco-based products. So although you thought F1 was done with big tobacco, it’s not quite as straight forward. I am sure these stories will continue to unfold during the 2020 season.

The big question I have is: Is it worth it? Both for the F1 teams and the actual sponsors.

As a sponsor, why would you spend so much money if you aren’t pushing your products? I certainly can’t reply to this on their behalf but by the sounds of things, it’s great PR and they are tapping into some of the oldest tricks in the book. You gain visibility at the highest level by showcasing the good you are doing with your CSR programmes/campaigns, and they get to stay in F1 without actually getting involved. And even when they get bad PR, it’s still free publicity at the end of the day. If the tobacco and nicotine industry wasn’t getting their money’s worth, I doubt they would continue. But one thing is for sure, it’s certainly no longer the Wild West and the budgets are no longer what they used to be.

As an F1 team, I think the answer is a little trickier. As you will know by now, to compete in F1 you need lots of money, and when the stakes are as high and big sponsors come knocking you will most likely sit down and listen to their ideas. I’m not sure if over time the controversy and stigma attached to tobacco will be worth it, especially with the younger drivers becoming increasingly vocal about what they stand for.

The Future of Title Sponsorships

Could alcohol be next and follow the same fate as big tobacco? A handful of liquor accompanies such as Heineken (F1 sponsor), Martini (Williams), Johnnie Walker (also an F1 sponsor) and Chandon ( McLaren) are all under scrutiny as sponsors. Especially by the WHO. And those that don’t seem to have ties with any alcohol brands do however have energy drinks as sponsors - namely Red Bull and Monster.

In some countries, this is already well underway. In France, for example, it’s already forbidden to favourably advertise tobacco and alcohol products at sporting events such as the F1 Grand Prix. And it’s not just tobacco and alcohol, energy drinks were banned completely in France until 2008 when the 12-year ban was lifted after the European Commission intervened.

The Rich Energy story that blew my mind

I can’t talk about energy drinks as F1 team sponsors and not mention Rich Energy. There are plenty of crazy stories around fake companies and products becoming title sponsors and having their logo plastered all over the F1 team cars - actually, this Donut Media video does a pretty good job at capturing some of the insanity around these fake brands.

One of the most recently talked about sponsorship fiasco is the Rich Energy vs. Haas story. There have been plenty of articles written about this story at length so I’ll leave you with this succinct debrief of events.

Firstly it’s worth noting that you would be hard-pressed to find Rich Energy sold anywhere (1), their website is hosted on Squarespace (2) and their bank balance was reported to be $770 in 2017 (3). None of this screams F1 sponsor.

The company first came about when Rich Energy’s CEO, William Storey, made an offer to Force India (now Racing point) as they went into administration. However, Storey wasn’t viewed as a viable candidate to be the owner of the team and was dismissed.

Then Rich Energy focused on getting a sponsorship deal with Williams F1 team for the 2019 season but instead agreed on a multi-year deal as title sponsor for the Haas F1 team through to the 2022 season - a deal estimated at $45.7 million according to Rich Energy. Apparently Storey never showed up to the meeting with Williams, and that was that.

However, and you probably saw this coming, the partnership ended prematurely in the mids of the 2019 season. Storey announced on twitter that the partnership was terminated citing poor on-track performances (during the British Grand Prix). Haas later confirmed the end of the partnerships and stripped the Rich Energy branding from the cars.

In May 2020, Rich Energy seemed to be back taunting the Williams F1 team again, only shortly after they announced that Rokit was no longer a main sponsor for the Williams F1 team. You couldn’t make this stuff up if you tried to.

It definitely feels like the smaller F1 teams seem to be at the mercy of wannabe F1 sponsors that at best use this opportunity as a publicity stunt or at worst hinder the reputation of these F1 teams. The planned 2021 budget cap might help prevent any such future sponsorship deals that sound too good to be true as the smaller teams won’t be struggling quite as much to fill the gap between their spending and that of the top teams like Ferrari and Mercedes.

🎙If you still need convincing, I invite you to listen to Will Buxton talk about his first F1 experience and his career as an F1 journalist.

“It was the most electrifying sound I had ever heard”

👉 Download your beginners’ F1 Lexicon here.

👉 Download the cheat sheet of drivers and teams for the 2020 season.