Engineering the impossible

McLaren’s radical bet on innovation spillover

Thank you for being here. You are receiving this email because you subscribed to Idée Fixe, the newsletter for curious minds. I’m Toni Cowan-Brown, a tech and F1 commentator. I’m a former tech executive who has spent the past five years on the floor of way too many F1, FE, and WEC team garages, learning about the business, politics, and technology of motorsports.

⏳ Reading time: 5mins

Here’s a sentence I never thought I’d write: Formula 1 pit stop choreography is now optimising pharmaceutical manufacturing lines, and race engineers are building machines to save the Great Barrier Reef.

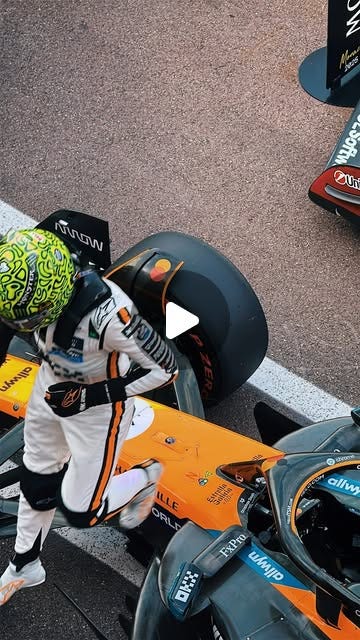

Welcome to McLaren Racing’s wildly unlikely last few years, where the same team chasing constructor championships (and has successfully done so, two years in a row, having just clinched the World Constructor Championship 25’ in Singapore and Lando Norris finally securing himself in the history of Formula 1 with his first World Driver Championship 25’ in Abu Dhabi) is simultaneously tackling coral restoration and the circular economy design.

It’s weird. It’s ambitious. McLaren’s sustainability playbook could redefine what innovation spillover means and what it looks like. And it might actually rewrite how we think about the relationship between elite motorsport and everything else.

Note: This piece, research and videos produced are part of a partnership in collaboration with McLaren Racing during New York Climate Week 2025.

Formula 1’s most unlikely project

How McLaren’s engineers went from on-track success to growing a million baby corals. Let’s start with the most surreal partnership: McLaren’s collaboration with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. I also had the pleasure of facilitating a discussion during NY Climate Week (at Goals House) between Kim Wilson, Sustainability Director at McLaren Racing and Anna Mardsen, Managing Director at the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

You would be forgiven if your immediate reaction was scepticism - another sports team greenwashing with a trendy environmental cause. But dig deeper, and it gets genuinely interesting. Not only that, the numbers and results so far are impressive.

McLaren Accelerator, the team’s in-house team of experts offering the know-how and expertise we apply to delivering results on the track, to our partners, is working with marine scientists on a project to accelerate coral reef restoration at scale and speed. They’re not just slapping a logo on existing research. McLaren engineers, along with 300 marine biologists, have helped build “Machine One” - a system designed to boost coral output from 100,000 to one million baby corals while slashing costs from AUD$10 to just $2 per coral.

Think about that economic shift for a second. Cost reduction at that magnitude doesn’t just make restoration feasible, it makes it scalable. And that’s pure F1 thinking: how do you make the impossible merely difficult, and the difficult routine? The machine is set for testing during November’s coral spawning season, applying the same iterative, performance-obsessed approach that shaves milliseconds off lap times to a problem that exists on geological timescales.

Circular by design, not by slogan

McLaren’s engineers are rewriting F1’s manufacturing model to highlight that performance and circularity are not mutually exclusive. The partnership with Deloitte UK on building a fully circular F1 car by 2030 is another fascinating pivot. Together with Deloitte, McLaren Racing is looking at ways to supercharge efforts in developing a circular F1 car and help unlock more opportunities for circular practices across the sport. In other words, McLaren is attempting something structurally different: reimagining the entire “take, make, dispose” model that has defined F1 since its inception.

In 2024, McLaren achieved 37% material circularity in their F1 constructor activities and pioneered the use of recycled carbon fibre in performance parts. That last part is crucial - performance parts (non-safety critical), not just cosmetic bits. They’re highlighting that recycled materials can meet the absurd tolerances and safety requirements of cars travelling at 350 km/h. And as ever, if it’s successful testing under the extreme pressure of an F1 race weekend, then we know it can be applied elsewhere - and not just on road cars.

The team trialled recycled carbon fibre at Silverstone in 2024 and Austin in 2023, which feels appropriately McLaren. And let’s not forget, they were the first team to race a fully carbon fibre chassis back in 1981. Forty-plus years later, they’re trying to close the loop on that same material.

Speed as a transferable skill

McLaren’s process engineering is now accelerating vaccine production - a real-world example of F1 innovation spillover. The Sanofi partnership might be one of my favourites because it’s so specific and measurable. Inspired by McLaren’s 2023 world-record pit stop, Sanofi optimised their manufacturing line changeovers and cut times by up to 40% through video analysis and standardisation. That’s not metaphorical collaboration - that’s literal technology transfer.

Think about the implications: the same optimisation processes that get four tires changed in 1.8 seconds are now accelerating pharmaceutical production. The skills are fungible. The mindset transfers. This is what genuine knowledge spillover looks like, and it’s happening in real-time. This way of thinking can easily be replicated and applied to so many different areas.

Fueling the Future, Literally

Sustainable aviation fuel as a test case for scaling real-world climate infrastructure. With support from partner Ecolab, McLaren funded one million US gallons of sustainable aviation fuel in 2024, covering 100% of their business travel by air across all racing series. The team also achieved a 23% reduction in emissions per race compared to 2023 and cut road freight emissions by 48%.

Here’s where scale matters: Individual companies buying SAF certificates helps, but McLaren’s commitment matters because it signals demand. SAF has the potential to cut aviation emissions by up to 90% compared to conventional jet fuel, but the market needs anchor customers to prove viability. Which is where the likes of McLaren Racing comes in. When high-profile organisations commit at this level, they’re not just reducing their own footprint; they’re helping build the infrastructure that makes alternatives viable for everyone else.

The case for Formula 1 as the world’s most unexpected innovation lab and it matters

One of my favourite things about Formula 1 since I started watching the sport back in 1991 is precisely this spillover of R&D and incredible innovations built by some of the most brilliant minds, into all these other spaces.

F1 has always been a laboratory for extreme engineering. Carbon fibre, hybrid powertrains, materials science, aerodynamics - the sport pushes everything to its absolute limit.

What McLaren are doing is systematising the spillover effect and applying the same marginal gains philosophy - obsessive focus on tiny improvements that compound into massive advantages - to problems well outside the paddock. They’re not waiting for innovations to accidentally drift into other industries. They’re actively translating race-day thinking into climate solutions, manufacturing efficiency, and materials innovation.

Is it perfect? No. Is there a brand benefit and positive PR? Obviously. But the projects are real, the metrics are specific, and the potential impact scales beyond what one racing team could achieve alone. When F1 engineering helps save coral reefs and optimises pharmaceutical manufacturing, that’s innovation arbitrage. And we should be seeing a lot more of it in the coming years - especially from within the Formula 1 ecosystem. McLaren’s Secret Weapon Isn’t Speed, It’s Systems Thinking

Fascinating look at systematic spillover versus accidental diffusion. The coral restoration cost drop from $10 to $2 per unit is the kind of manufacturing efficiency gain that only makes sense when you have F1 engineers obsessed with marginal improvements. What clicks for me is how they're applying extreme constraint thinking (regulations, safety, speed) to problems that traditionally haven't had those pressures. The Sanofi pit stop analysis transfer is elegent because it's so literal, not metaphorical innovation transfer. Would love to see more data on how much faster circular materials R&D moves under F1 time pressures versus traditional automotive cycles.