Did you Know Playboy Had a Braille Edition?

What It Meant Then and Why It Matters Now

Thank you for being here. You are receiving this email because you subscribed to Idée Fixe, the newsletter for curious minds. I’m Toni Cowan-Brown, a tech and F1 commentator. I’ve spent the past five years on the floor of way too many F1, FE, and WEC team garages, learning about the business, politics, and tech of motorsports. I hope you’ll stick around.

Playboy's Braille Edition

This isn’t directly related to sports, politics or Formula 1 but very much indirectly related. One of the main reasons I created Sunday Fangirls - The Untapped Billion of sports - years ago was partially to reclaim the word ‘fangirl’ - a word too often used to ridicule and shame young girls and women in their approach to fandom when in reality they are subject matter experts. It was also a platform to highlight the Untapped Billion of this industry and how they are changing the game for the better. It’s an ode to the sports fan everywhere that didn’t fit the traditional stereotype we had been showing front and centre for too long, but no longer. And the story about Playboy’s braille issue is not too dissimilar - it’s about diversity, inclusion, resilience and taking back control.

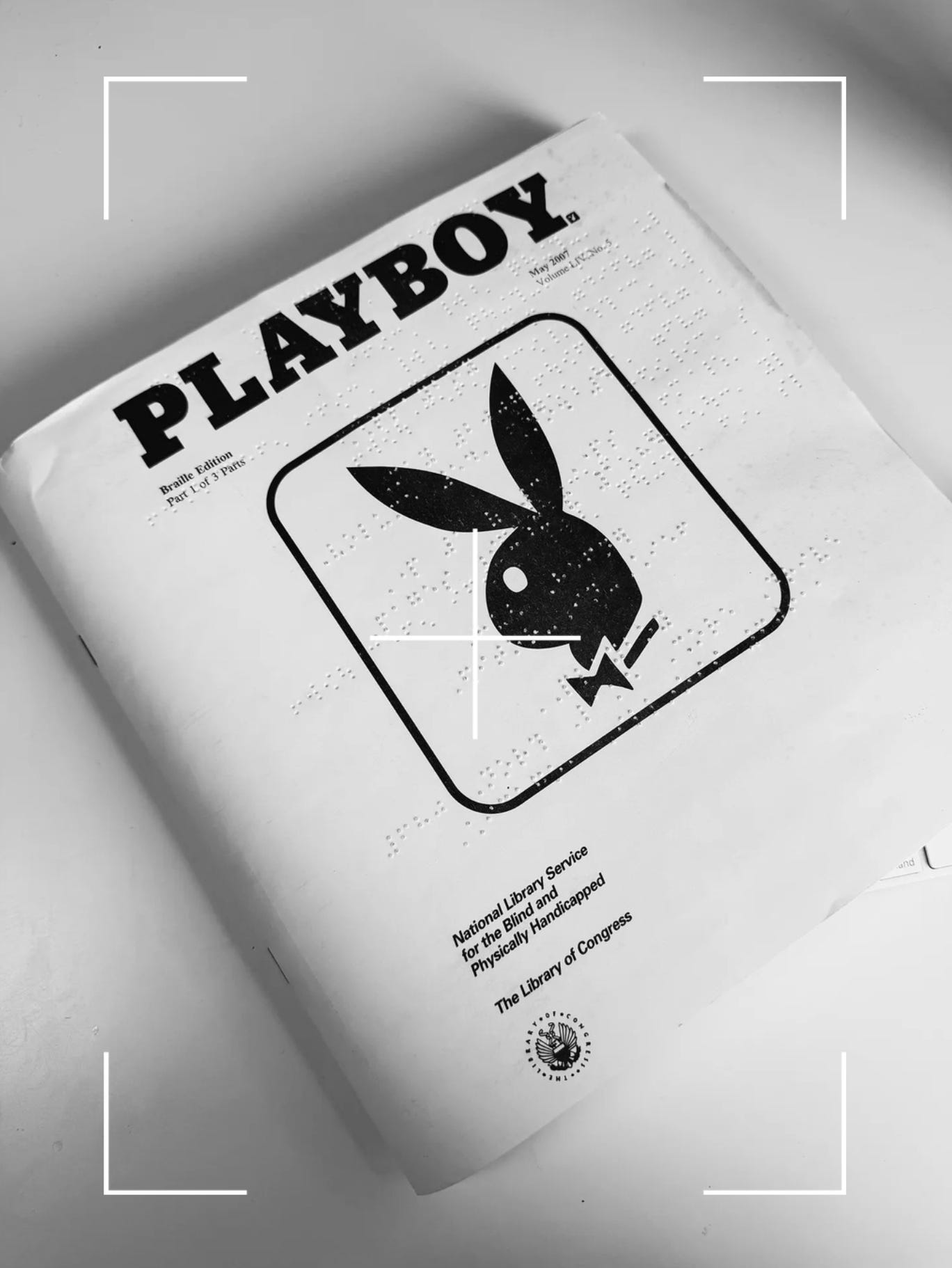

A few weeks ago I got my hands on something I had forgotten I had bid on on eBay and won. It’s something I had been eyeing for a while. Something unusual and something that I couldn’t get out of my mind. I couldn’t shake this feeling that it would be an important part of history one day - now more than ever.

In 1970, Playboy made an unexpected move: it became the first adult magazine to be published in Braille, available through the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS). This wasn’t a gimmick. It wasn’t a stunt. It was a statement about accessibility and the right to read.

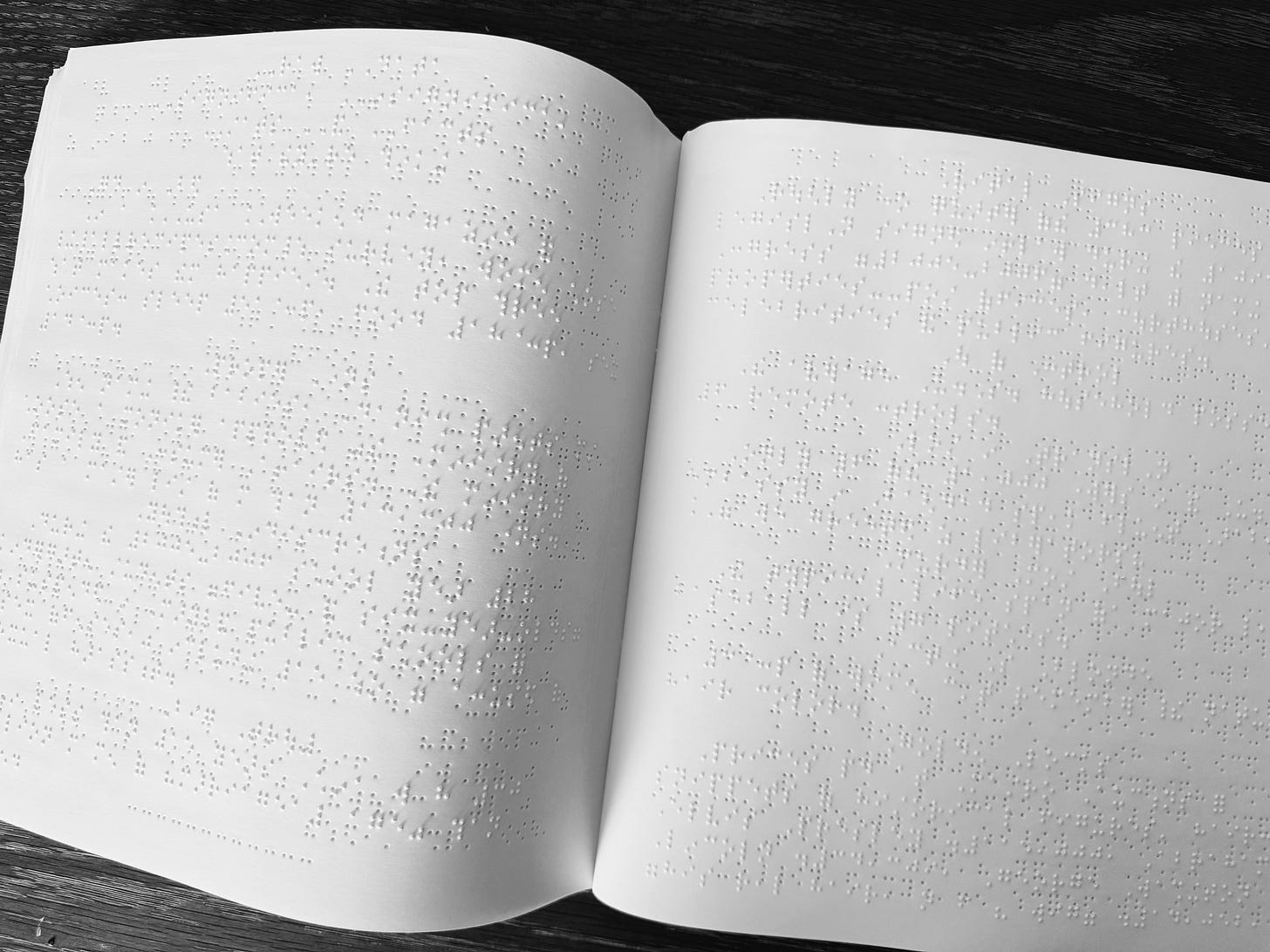

The Braille edition contained no images (obviously) - just text. But that text included some of the best journalism, fiction, and political commentary of its time. I’m surprised at how few people know just how good some of the articles published in Playboy actually were. Readers who were blind or visually impaired could access the same long-form interviews, literary contributions, and essays as anyone else would, reinforcing the idea that culture and intellectual discourse should be available to all.

Yet, as progressive as the initiative was, it didn’t come without controversy. Many conservatives and religious groups in America were outraged, arguing that taxpayer dollars (since the NLS was federally funded) should not be used to distribute what they saw as an “adult” magazine. But this outrage overlooked a fundamental truth: Playboy was never just about the centrefolds. It was so much more and Jameela Jamil’s 2020 issue, for me anyway, highlighted this fact (more on that in a bit).

How the Braille Edition Came to Be

The idea for a Braille edition of Playboy didn’t come from a boardroom - it came from visually impaired readers who wanted access to the magazine’s serious journalism and literary work. At the time, no accessible version existed, and they felt excluded from a cultural conversation they had every right to join.

After persistent advocacy, the National Library Service (NLS) - which provides free reading materials for blind and visually impaired Americans - added Playboy to its catalogue, alongside titles like The New York Times and Time Magazine.

The backlash was immediate. Critics argued that a federally funded program shouldn’t distribute a magazine known for adult content, even though the Braille edition contained no images - just text. In 1985, Senator Jesse Helms led a campaign to defund it, calling it a misuse of taxpayer dollars. But the NLS and disability rights advocates pushed back, defending access to information as a fundamental right. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately allowed Playboy to remain in circulation - calling any attempt to block it a form of government censorship.

It was a win for free speech, accessibility, and the principle that equal access to culture shouldn't depend on someone's comfort level. Each Braille edition of Playboy contained: Investigative journalism on politics, technology, and culture. Interviews with major figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Jimmy Carter. Literary fiction from authors such as Margaret Atwood, Gabriel García Márquez, and Ray Bradbury. Editorials and essays on social justice, free speech, and civil rights. Humour and satire pieces, which were a major part of the magazine's identity.

By the 1990s, it was estimated that hundreds of Braille copies were in circulation each month, a significant number for a niche publication serving a specific audience.

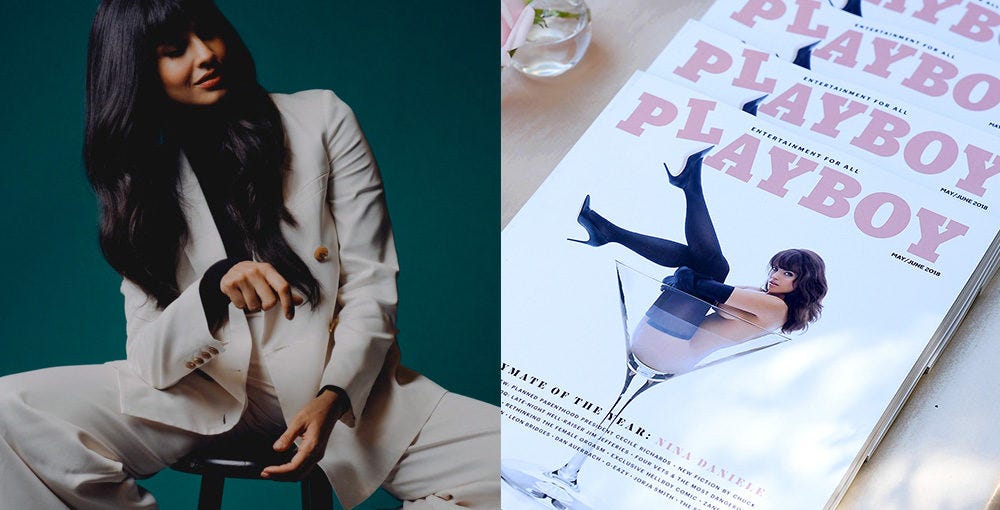

Jameela Jamil’s Playboy Cover: A Radical Rethink of Sexy

In 2020, Jameela Jamil appeared in one of the final print editions of Playboy and it wasn’t your typical Playboy shoot. She was fully clothed. No nudity. No male gaze. Just her; powerful, confident, and in full control of how she was seen.

The cover was part of the magazine’s "Speech Issue", which aimed to celebrate freedom of expression, identity, and body autonomy - a major pivot from the brand's traditional image. This was a very intentional choice. It was part of a rebranding effort led by Playboy's younger, more progressive leadership team who were trying to reconcile the magazine’s complicated legacy with a new era of feminism, inclusion, and self-expression.

This edition forced the conversation and in an era where representation, inclusion, and agency matter more than ever, that cover wasn’t just another glossy page. It was a line in the sand.

Why It Matters Today

Fast forward to the present, and the fight for accessibility and inclusion is under attack once again. Across the U.S., Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs are being dismantled in corporations, universities, and public institutions. These initiatives were designed to ensure access to opportunities, resources, and representation for marginalized groups - including people with disabilities.

The argument used against DEI today - claiming it’s unnecessary, excessive, or even “divisive” - echoes the same rhetoric used against the Playboy Braille edition in the 1970s and ‘80s. The same forces that fought to limit access to reading material are now fighting to eliminate DEI under the banner of “anti-woke” sentiment. But at its core, this is about power and control over who gets access to information.

The Playboy Braille edition was never just about Playboy. It was about the fundamental right to access knowledge, ideas, and culture - no matter who you are. Today, as we see hard-fought gains in accessibility and inclusion being rolled back, it’s worth remembering this fight is nothing new. But history also shows us that progress isn’t easily erased.

After all, if a magazine best known for its centrefolds could push the boundaries of accessibility, imagine what we can accomplish when we refuse to let those barriers stand.

From Braille to Jameela: The Fight for Access, Redefined

The Playboy Braille edition and Jameela Jamil’s 2020 cover might seem worlds apart - one from the analogue 1970s, the other from the digital era of social justice and online advocacy. But at their core, both moments asked the same radical question: Who gets to participate? Who gets a voice? Who gets to be included in the conversation? And more importantly: On whose terms?

In 1970, blind readers demanded access to culture that was often denied to them - and Playboy, of all places, became a symbol of that fight. It wasn’t about the nudity. It was about not being excluded from cultural and intellectual life.

Fifty years later, Jameela Jamil redefined what it means to appear in Playboy - fully clothed, unsexualized, and unapologetically vocal. Her cover wasn't about visibility for the sake of allure. It was about being seen on her own terms. About reframing who defines sexy, power, and self-expression. Both moments challenged the legacy of a magazine often associated with objectification, and instead used that very platform to demand equity, autonomy, and voice.

🔗 The Man Behind a Champion: Anthony Hamilton | Culture of Sport

The cameras didn’t catch it for long, but it was one of the most powerful moments of the Australian Grand Prix. As Isack Hadjar stood shattered in the paddock, his F1 debut wrecked before it truly began, Anthony Hamilton stepped forward. Read here.

🔗 The Battle for the Bros | The New Yorker

By the time I landed at LAX and switched my phone out of airplane mode, Hasan Piker had been streaming for three hours. I put in an earbud and watched as I filed off the plane. Visible behind him were walls of framed fan art, a cardboard cutout of Bernie Sanders sitting in the cold, and Piker’s huge puppy, Kaya, taking a nap. Read here.

🔗 On Sabrina Stanley’s OF deal and the financial realities of a professional trail runner | Trailmix

Seems the athlete sponsorship rodeo hasn’t left town yet with both Riley Brady and Sabrina Stanley announcing their new sponsor this week. There is a bigger story that surrounds Sabrina’s OnlyFans sponsorship that needs unpacking - the current reality of athletic sponsorship isn’t working and athletes are starting to realise. Read here.